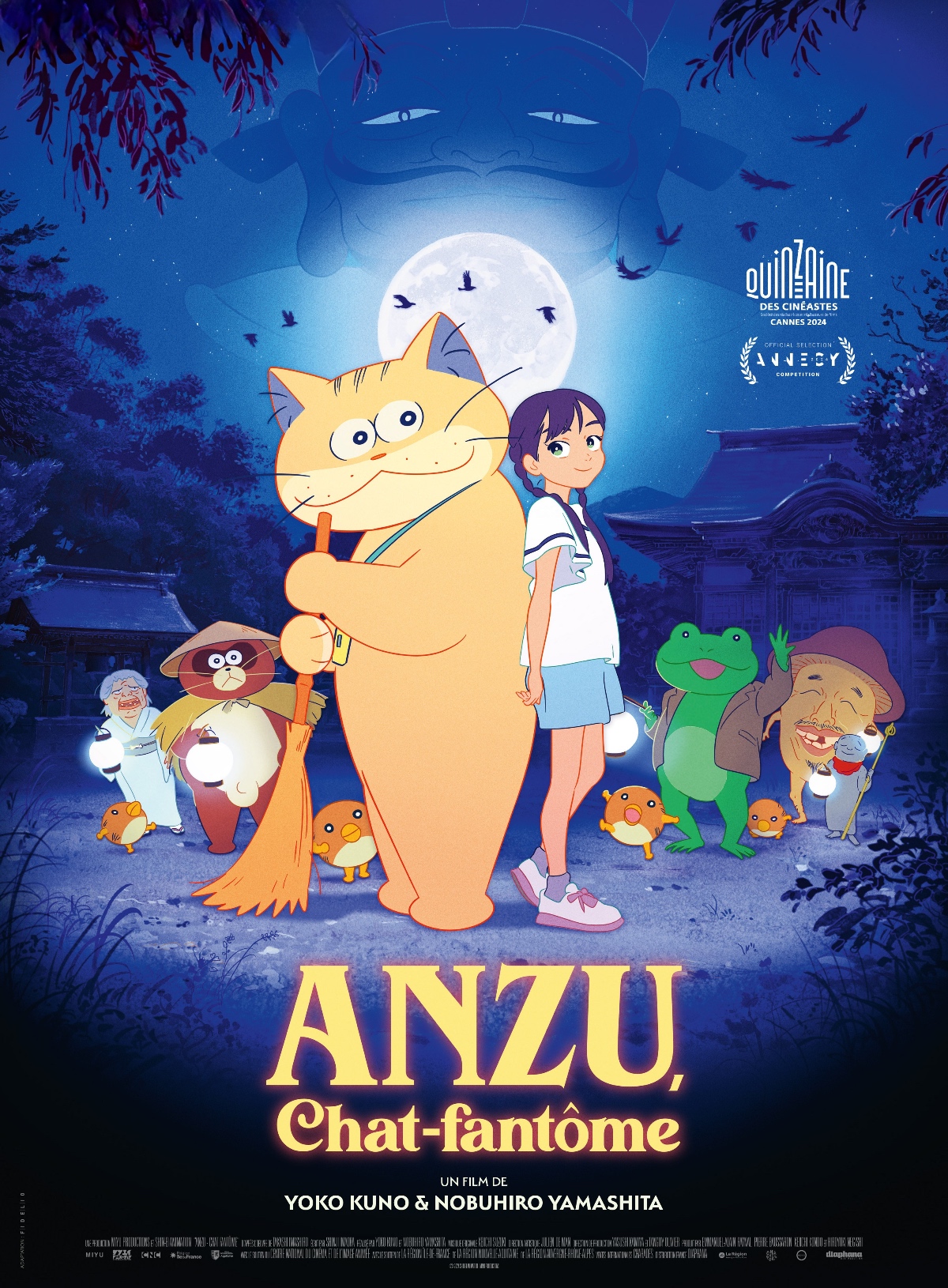

Ghost Cat Anzu (2024): A Quirky and Endearing Anime Adventure

When 11-year-old Karin is left at her grandfather’s temple, the last thing she expects is a guardian like Anzu—an irritable, self-centered ghost cat.

Ghost Cat Anzu

Original title: Bakeneko Anzu-Chan

Directors: Nobuhiro Yamashita & Yôko Kuno

Country: Japan

Ghost Cat Anzu is the brainchild of Nobuhiro Yamashita, even more so than co-director Yôko Kuno, who animated the film. Though Yamashita’s background is primarily in live-action filmmaking—having directed films like Hard-Core aka Hâdo koa (2018) and Karaoke Iko! (2023)—he fell in love with Takashi Imashiro’s manga, initially published in 1981, and knew he wanted to adapt it into a feature film. When Yamashita met producer Keiichi Kondô, he pitched the idea, and Kondô saw its potential. Kondô introduced Yamashita to one of his regular collaborators, animator Yôko Kuno. The partnership clicked, and the project took shape from there, blending Yamashita’s storytelling with Kuno’s animation talents.

When exploring Yamashita’s body of work, it is clear why he liked the manga Ghost Cat Anzu. From his debut Hazy Lifeaka Donten seikatsu (1999) to films like The Drudgery Train aka Kueki ressha (2012) and Tamako in Moratorium aka Moratoriamu Tamako (2013), Yamashita has consistently focused on characters who do not conform to societal expectations. His leads are often flawed and aimless but never beyond redemption. Ghost Cat Anzu continues this thematic exploration. Anzu (voiced by Mirai Moriyama) is no ordinary cat; he is an anthropomorphic figure involved in gambling, scamming deities, and facing supernatural dangers. However, he balances selfishness with heroic moments, like when he risks his life to save his friends.

Yamashita also adds a new layer to the story by introducing Karin (Noa Gotô), a character absent from the original manga, which focuses on the cat’s interactions with the locals. This 11-year-old girl with a troubled family background becomes a co-protagonist alongside Anzu, the ghost cat. Hardened by the loss of her mother and her father’s neglect, she is a complex and thorny character who often lashes out and mirrors her father’s questionable moral compass when she tries to extort money. Yet, beneath her tough exterior, Karin is capable of moments of vulnerability, making her a profoundly human character despite her struggles.

The dynamic between Anzu and Karin forms the emotional core of the film. Karin’s father is an unreliable man burdened by debt, who leaves her at her grandfather’s monastery, where Anzu resides. Despite the cat’s irritability and self-centered nature—like spending the child’s pay on pachinko, a famous Japanese gambling game—he becomes a more reliable figure in Karin’s life than her father. The unlikely bond between the grumpy cat and the manipulative young girl shapes the narrative, subtly examining how even flawed or unconventional role models can leave a positive impact.

“What I love about the manga is how the artist treats the characters as real human beings—flawed, with both positive and negative traits. They’re not superheroes,” Yamashita told me when I met him and Kuno (who brought along a plush Anzu) at the poolside bar of Hotel Melià following their film’s screening at the 57th Sitges Film Festival. They had just finished lunch and were tipsy from enjoying a good amount of alcohol, which loosened them up to talk about their passion project.

However, the outsider aspect is not just about the characters’ personalities but—perhaps even more importantly—about their economic status in the 1980s. “I appreciated how the manga focused on a side of Japanese society often overlooked—the poor,” Yamashita explains. “In the 1980s, most people lived in a ‘bubblegum’ world, but Kondô was brave enough to highlight the struggles of the less fortunate during this era and help them find justice.”

“Bubble” culture in Japan refers to a period of exuberant consumerism, colorful entertainment, and widespread economic optimism, where the media often portrayed an idealized, upbeat, and affluent lifestyle. This phenomenon was primarily driven by Japan’s unprecedented growth in asset prices, stock markets, and real estate following the country’s manufacturing industry surge in the 1960s and 1970s. Easy access to credit led to massive speculative investment; companies, individuals, and financial institutions began borrowing heavily to invest in real estate and stocks, which led to more disposable income and further inflated prices, alongside the rise of high-end department stores, flashy consumer electronics, fashionable goods, urbanization, and “city pop” (a music genre featuring optimistic lyrics about love, freedom, and carefree living, set against the backdrop of a high-tech, cosmopolitan Japan). Even anime and manga during this period reflected this shiny, optimistic outlook, focusing on futuristic worlds or their characters’ rich, cosmopolitan lives.

This “bubble” economy left rural communities, blue-collar workers, and marginalized urban residents struggling to keep up. Rural depopulation, caused by younger generations moving to cities for better job opportunities, led to socially isolated communities and shrinking local economies. Certain marginalized groups, such as burakumin (descendants of historical outcast communities), Korean-Japanese, and other ethnic minorities, faced discrimination and limited economic opportunities during this time. The growing focus on corporate life and success also pushed many middle and lower-income employees to their physical and mental limits, leading to karōshi, or death from overwork. This relentless pursuit of success often put enormous pressure on workers to maintain the image of upward mobility and wealth, even if they could not fully participate in the lifestyle advertised by the “bubble” economy.

The unsustainable asset price inflation eventually burst in the early 1990s, but the effects on Japan’s poor were profound. Companies marginalized temporary and contract workers, and many lost their jobs or faced wage cuts. Unfortunately, the social safety net in Japan was not robust enough to cushion the fallout for everyone.

The lived realities of people who struggled to make ends meet were rarely represented in mainstream media, making Ghost Cat Anzu a refreshing exception. While the manga and anime touch on the economic challenges faced in 1980s Japan, they approach these issues primarily through personal and familial struggles rather than focusing directly on poverty. This perspective offers a more intimate glimpse into the lives of characters not part of that economic boom navigating the complexities of survival in a rural town.

These themes are precisely why Ghost Cat Anzu resonates more with a niche audience than the mainstream and took over ten years to get off the ground. “The manga is relatively obscure in Japan; it’s certainly not among the top titles,” Yamashita explains. (It currently ranks around #4894 on MyAnimeList with a popularity score of #9730.) “What drew me was the unique perspective on Japanese society and the focus on personal and familial struggles amidst economic hardships. Oddly enough, I’m not even a fan of cats and have never owned a pet, so that wasn’t what resonated with me,” he adds.

In contrast, Kuno’s love of cats allowed her to look beyond the political undertones of the manga. She brought this warmth and freshness into her art, with each frame standing out like a unique piece with soft pastel colors and detailed brushstrokes. Her sensibilities merge perfectly with Yamashita’s more grounded, slow-paced style. Additionally, Kuno’s love for the source material, her background in 2D and 3D animation, her work as a mangaka, and her expertise in rotoscoping (a technique where animators trace over live-action footage) made her a perfect collaborator for a film like Ghost Cat Anzu.

Yamashita and Kuno’s decision to use rotoscoping for Ghost Cat Anzu makes perfect sense, given Yamashita’s live-action background and the film’s manga origins. Rotoscoping—a technique used in anime like Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade aka Jin-Rô (1999) and The Flowers of Evil aka Aku no Hana (2013)—helped them balance realism with supernatural elements. While many live-action manga adaptations featuring life-sized animals use CGI (like in 2014’s Kiki’s Delivery Service aka Majo no takkyûbin) or puppetry (such as 2008’s Pussy Soup aka Neko râmen taishô), rotoscoping allowed the directors to keep the grounded undertones while capturing the quirky, feline traits of an anthropomorphic cat, like running on all fours or grooming itself. (You can find side-by-side comparisons of these live-action and animation scenes on YouTube.) Kuno also occasionally switches to traditional animation during action-heavy scenes and the playful montage that shows how a stray cat became a supernatural oddball.

Thanks to Yamashita and Kuno’s combined talents, Ghost Cat Anzu delivers a surreal, childlike view of dark, complex themes that mainstream media often avoids—a unique experience that will resonate with those seeking something beyond conventional animation.

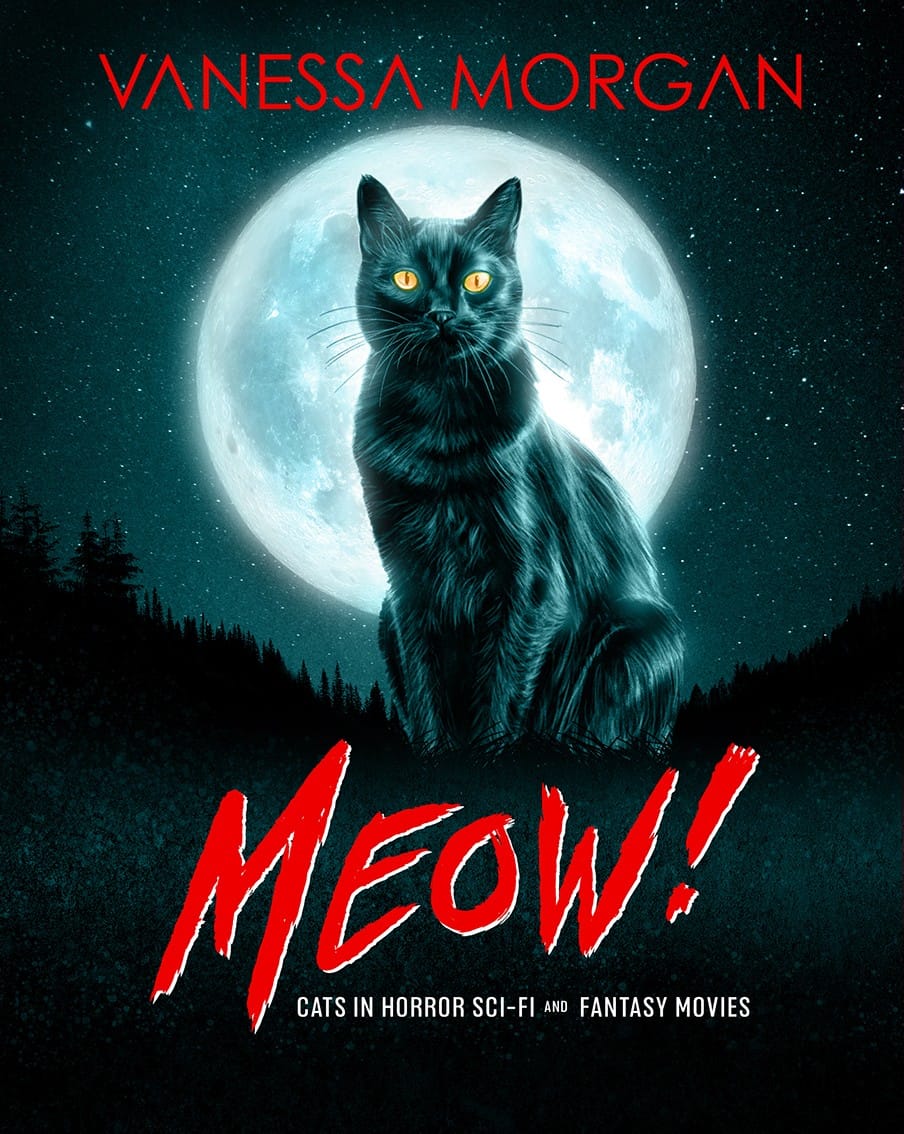

This essay on Ghost Cat Anzu (Bakeneko Anzu-Chan) was previously published in the book Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies.

About the author

Vanessa Morgan is the editor of When Animals Attack: The 70 Best Horror Movies with Killer Animals, Strange Blood: 71 Essays on Offbeat and Underrated Vampires Movies, Evil Seeds: The Ultimate Movie Guide to Villainous Children, and Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies. She also published one cat book (Avalon) and four supernatural thrillers (Drowned Sorrow, The Strangers Outside, A Good Man, and Clowders). Three of her stories became movies. She introduces movie screenings at several European cinemas and film festivals and is also a programmer for the Offscreen Film Festival in Brussels. When she is not writing, you will probably find her eating out or taking photos of felines for her website, Traveling Cats.

Pin the Ghost Cat Anzu (2024) movie poster!

Sounds like a great movie.

Thank you for joining the Awww Mondays Blog Hop.

Have a fabulous Awww Monday and week. ♥