Mr. Patman (1980): When reality crumbles, a cat is the only thing left

In Mr. Patman (aka The Crossover, 1980), a night-shift orderly at a psychiatric hospital begins to question his own sanity as he gets drawn into his patients’ world. His only anchor to reality is his cat, Patty.

Mr. Patman

Alternate title: The Crossover

Director: John Guillermin

Country: Canada

Mr. Patman is one of the most fascinating and heart-wrenching films to come out of the late 1970s Canadian tax-shelter boom, a period which started in 1974 and ended in 1982, during which numerous films were made primarily for their CCA (Capital Cost Allowance) tax benefits rather than artistic merit. However, thanks to the sheer volume produced, the era also gave birth to many memorable genre movies: The Brood (1979), Prom Night (1980), Terror Train (1980), Death Ship (1980), Humongous (1982), Black Christmas (1974), and Curtains (1983).

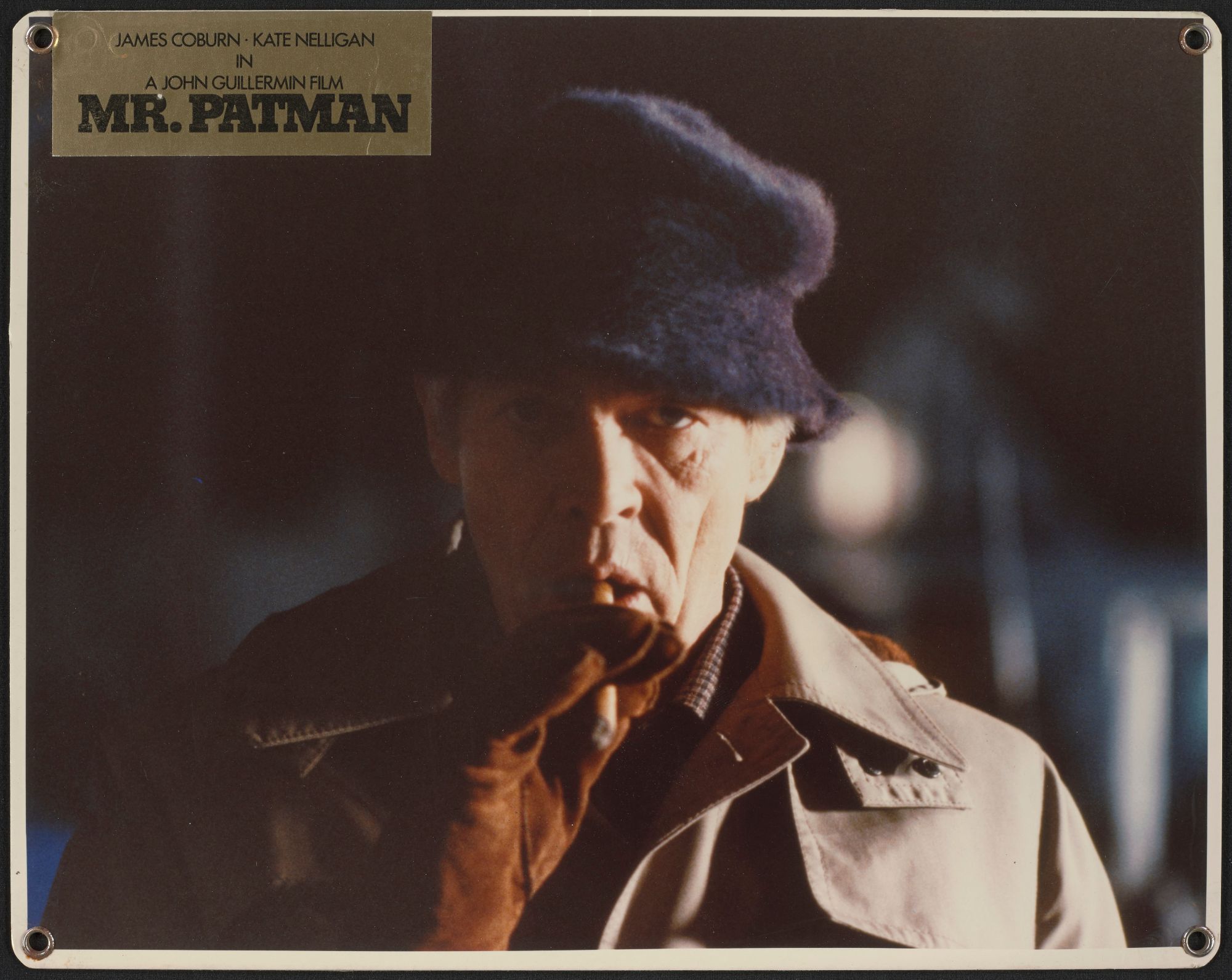

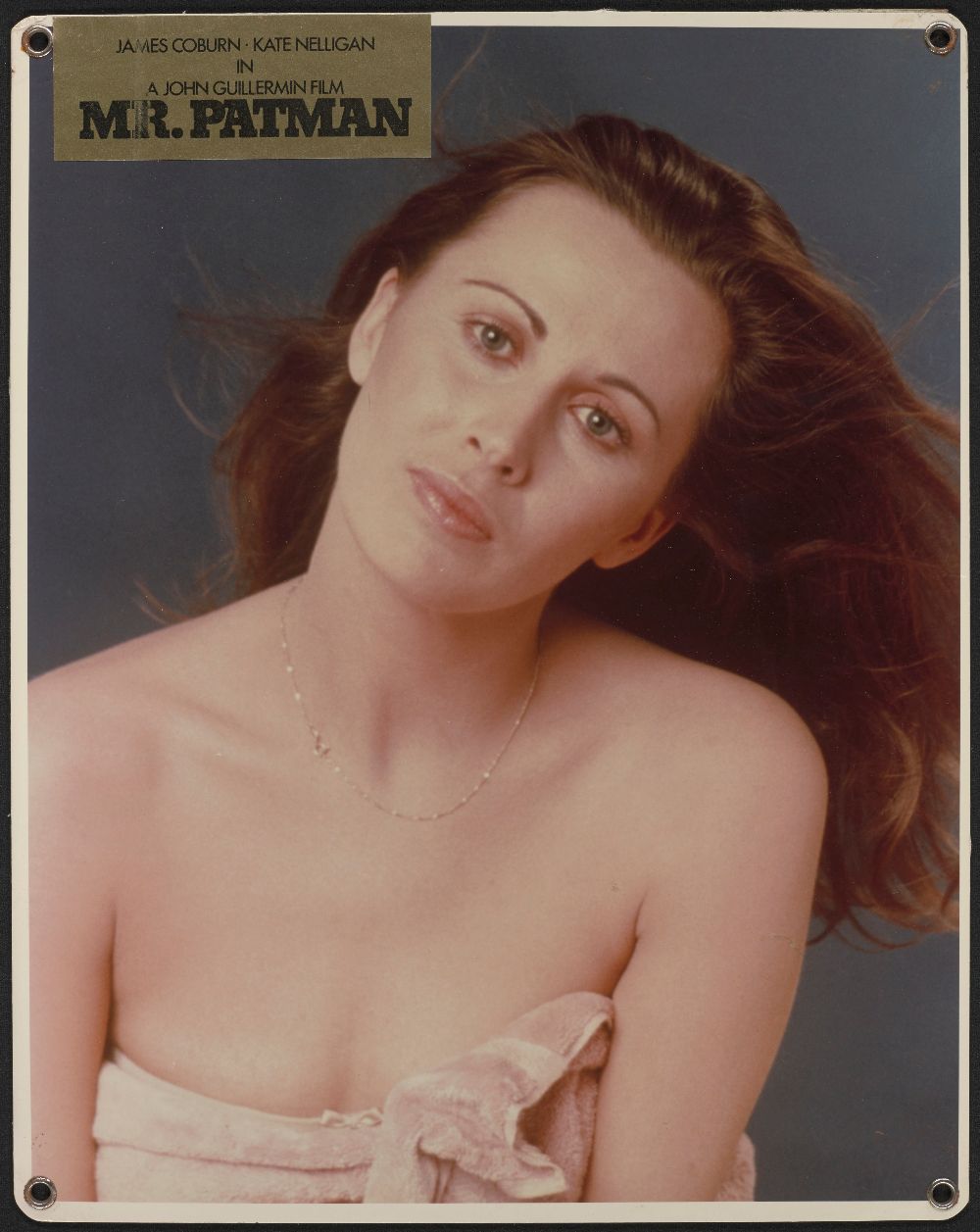

Despite the involvement of director John Guillermin (The Towering Inferno, King Kong, Death on the Nile) and influential actors like James Coburn (The Great Escape, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) and Kate Nelligan (Academy Award nominee for Dracula and The Prince of Tides), Mr. Patman never received a theatrical release in Canada. Instead, it was aired by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, after which the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce took control of the film. Still, their efforts at distributing it were largely unsuccessful. Today, finding a copy of Mr. Patman is rare and expensive, usually limited to VHS tapes.

The controversial production is one of the reasons why Mr. Patman struggled to find its footing. Nelligan described the movie as a nightmare. After a dispute with producer Bill Marshall, a founding member of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), one of the screenwriters removed his name from the film. Actress Karen Black filed a lawsuit against Marshall for breaching a verbal agreement to cast her, costing him $62,500, and editor David Nicholson shortened Vince Hatherley’s original edit of 111 minutes to 97 minutes, a change that Coburn admitted did not benefit the story.

The film also underwent several title changes during its development, hindering its promotion. During production, it was known as Midnight Matinee, The Bed Next to Mine, Man in White, The Optimist, and Patman but was later released as Crossover and Mr. Patman.

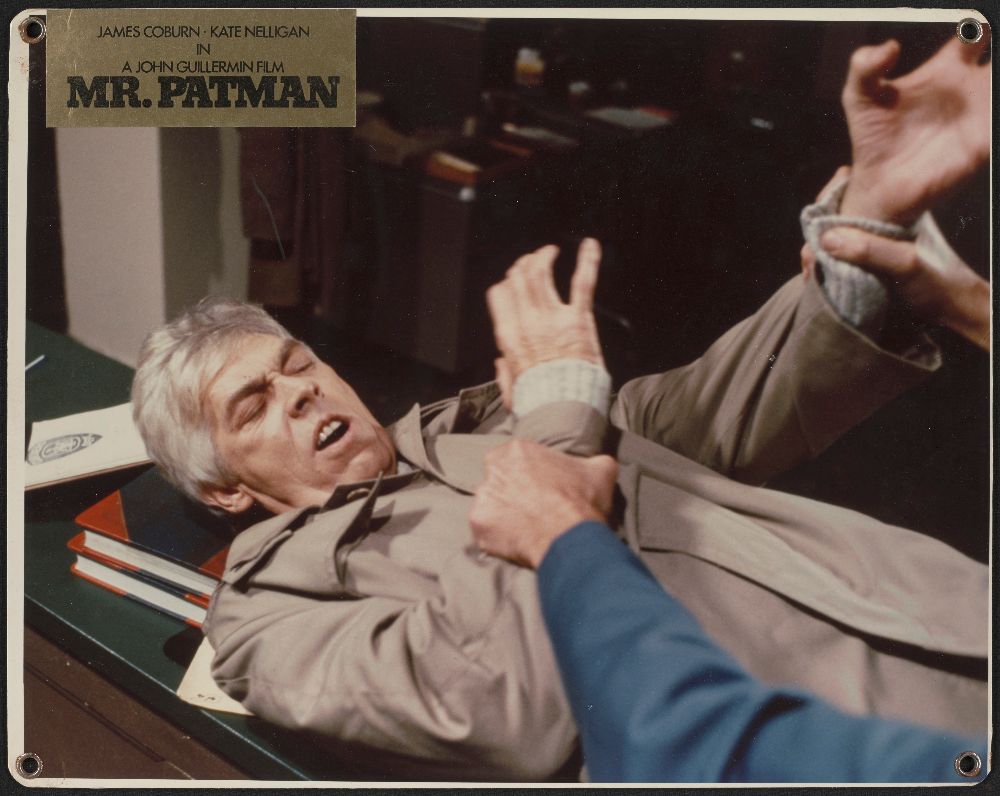

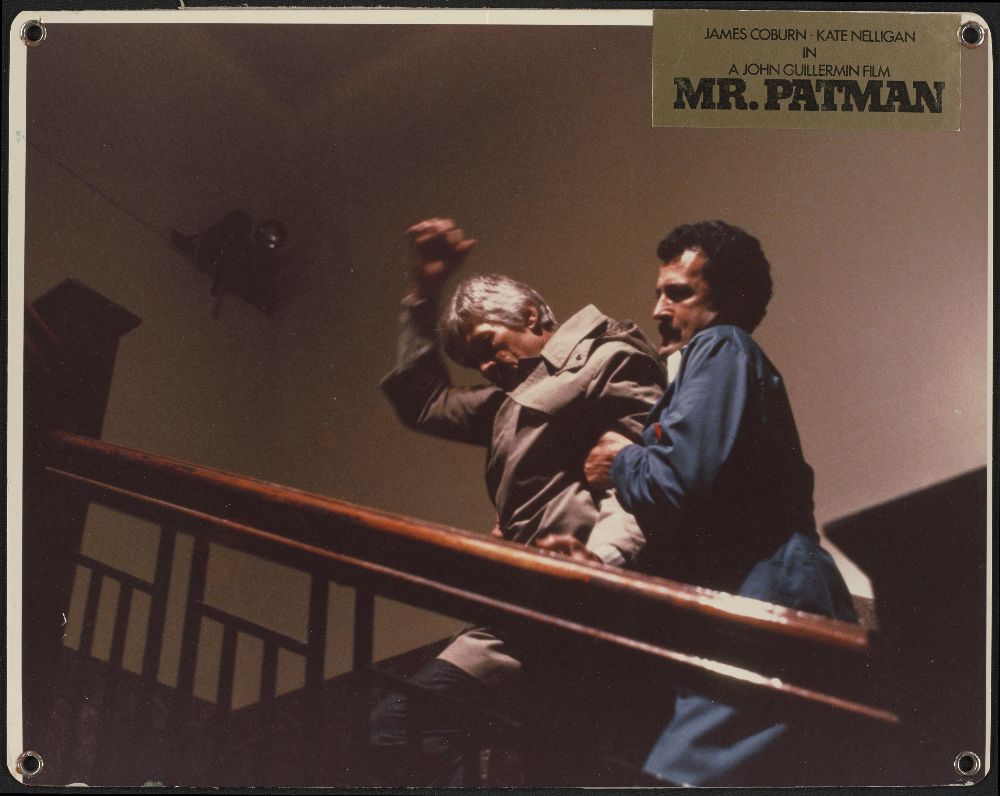

However, Mr. Patman went under the radar for another reason. The film is grim, with complex themes, an unusual payoff, and little action. Yet, it is also intriguing and heartbreaking. Inexperienced viewers might not enjoy this film, but those seeking something different and less straightforward will find Mr. Patman a true discovery.

The titular character, Mr. Patman, is a male nurse working the night shift in a psychiatric ward of a Vancouver hospital. The movie opens with Paul Hoffert’s gloomy rendition of “Hush, Little Baby,” a lullaby that promises children their parents will do anything to make them happy. It is a subtle yet poignant reflection of Patman’s dedication to his patients. Next, we see Patman hesitating to board the bus to work—a scene that may seem insignificant but becomes profoundly meaningful when connected to his life-changing decisions in the film’s final moments.

The movie meticulously details Patman’s routine and interactions with his patients, highlighting his compassionate care and ability to relate to them. It stands in stark contrast to the dehumanizing treatment by the other hospital staff, who often forget patients’ names or make critical decisions, like ordering heart surgery, without informing them. Ultimately, however, he feels powerless to effect any real change.

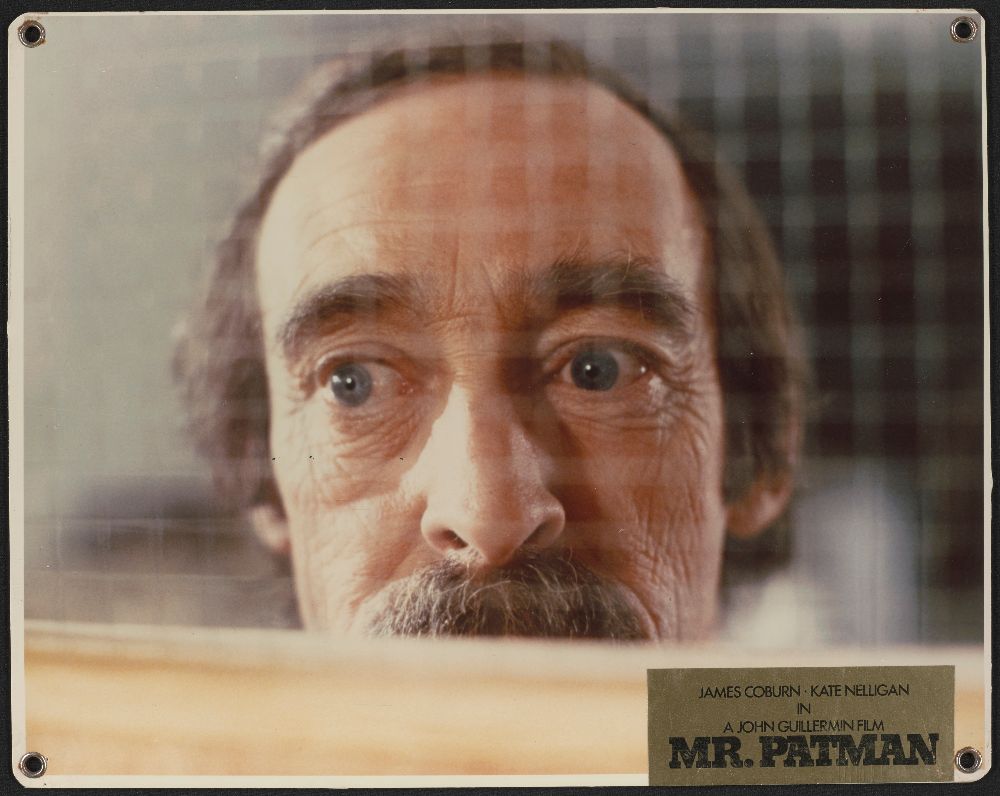

The film quickly delves into themes of compassion fatigue, the emotional toll of caregiving, and the fine line between professional detachment and genuine care. Despite Patman’s competence, he is haunted by feelings of inadequacy and purposelessness. He is affected by the plight of certain inmates, whose suffering and lack of improvement make him doubt the impact of his efforts. The suicide of his patient and friend Monica (Lynne Griffin) brings these latent frustrations and helplessness to the surface, exacerbating his emotional unraveling.

Another significant theme in the film is Patman’s loneliness. His peers respect him, but he is not well-understood or closely connected to others. Even though several women have feelings for him, especially his co-worker Mrs. Peabody (Kate Nelligan), he is convinced that love only happens to the lucky few. “That’s like asking for a star of your own,” he comments. His only true friend is his aging cat, Patty, whom he loves dearly. Patty is the only one he truly opens up to, and her well-being is his top priority. He even cooks for her. Their bond of trust is evident in several scenes, such as when Patman helps her off a roof, and the animal trusts him enough to jump. The fluffy ginger symbolizes Patman’s emotional dependency. It acts as a confidant, highlighting his struggle with loneliness and his tenuous grasp on reality, especially as his mental state declines and he starts experiencing paranoia and delusions. If their names sound similar, it is because Patty is an extension of Patman; she is his only connection to sanity and the real world.

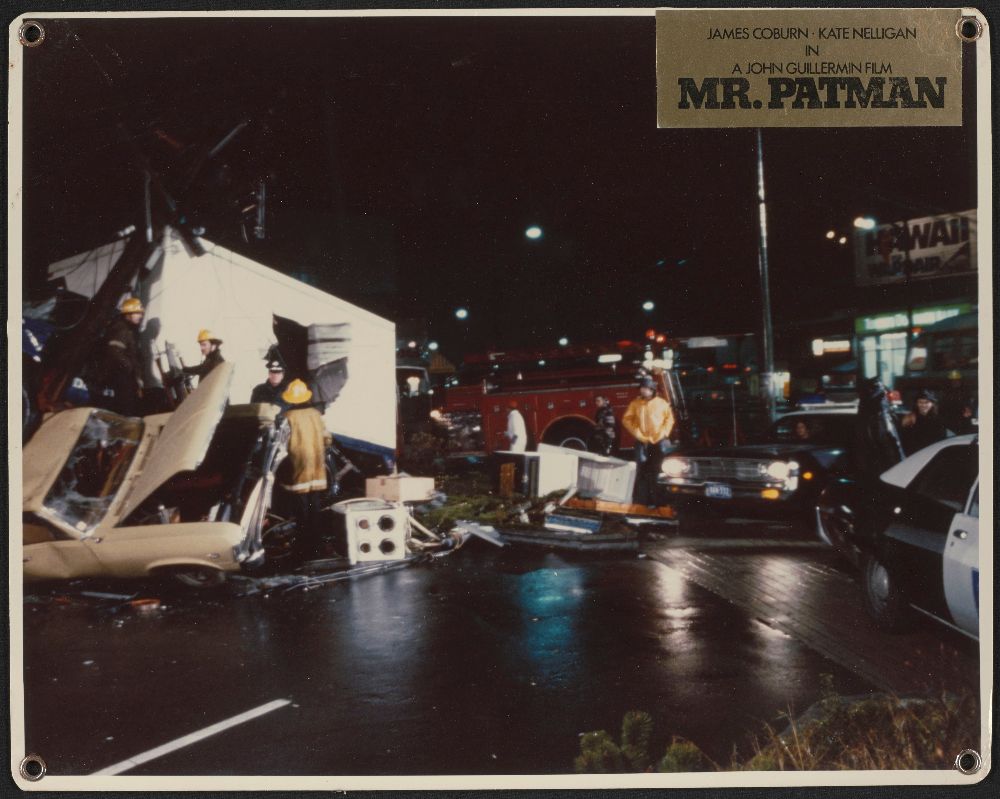

In the third act, Patman undergoes a period of reflection and re-evaluation and decides to quit his job at the hospital. Peabody offers him a chance at love and asks him and Patty to join her on a trip to California. Although he is hesitant and doubts that life can improve so quickly, he agrees to go. Wanting to save his patient, Mrs. Beckman (Candy Cane), from unwanted heart surgery, he brings her along on the trip. Unfortunately, during the journey, Mrs. Beckman’s heart fails. Peabody tells Patman she will drop the older lady off at the hospital, claiming she found her on the street and that she died before they arrived. When Patman realizes Mrs. Beckman passed away because of his poor judgment, he understands where he truly belongs. Peabody promises to return for him after she has sorted things out, and Patman agrees, saying, “Okay, but I have to say goodbye to a friend first.”

Back home, he euthanizes his furry companion. As he prepares the fatal injection, he tells her she will never survive on the streets, especially at her age and after the fine life he has given her. As she is dying, he holds her close and tells her how much he loves her. He then buries her in the garden.

The act of giving Patty a fatal injection carries deep symbolic meaning. First, it reflects Patman’s psychological collapse and the culmination of his existential despair. The cat is Patman’s closest companion and emotional anchor. By euthanizing it, Patman symbolically severs his last connection to sanity and emotional stability. The act represents his final descent into despair.

It also reflects the profound powerlessness and hopelessness permeating his life. The death of the cat is so brutal because it is unnecessary. We see an easy way out for both of them. Patman, however, is blind to that solution. Like the patients he cares for, Patty becomes a victim of his deteriorating mental health. It mirrors Patman’s feelings of being overwhelmed and out of control, both within the environment of the psychiatric ward and within his personal life. It underscores his loss of hope and belief in improving his circumstances. Patman resorts to the only action he feels he can control.

As promised, he meets Peabody a little later. However, he is not ready to start a new life with her. This time, he asks her to take him to the hospital, where he decides to become one of the patients. “Maybe one day,” he tells her as he walks inside the ward and takes place in an empty bed near the other residents of the psychiatric unit.

The film is a slow burn, and it takes a while for its emotional impact to take full shape. One of the most surprising aspects is its refusal to provide a resolution of psychological growth or a happy ending, as many films do. Instead, it stays true to the reality that most people find it easier to remain in their comfort zones, even if they are filled with madness and unhappiness. When Patman gets a chance at a better life with Peabody, he refuses because he does not believe in the possibility of change and love. He returns to the familiarity of the hospital’s insanity.

Yet, in a way, there is growth because there is a sense of acceptance. Patman finally acknowledges his fragile state and pursues what he wants instead of what others think is good for him, even if his decisions do not appear logical to most people. This lack of resolution and the embracing of hopelessness likely made it hard for the film to find an audience. It is not an easy watch, but its emotional impact is tremendous. The final scenes, in which Patman euthanizes his beloved Patty and becomes a patient himself, are devastating—perhaps among the most impactful in cinema history.

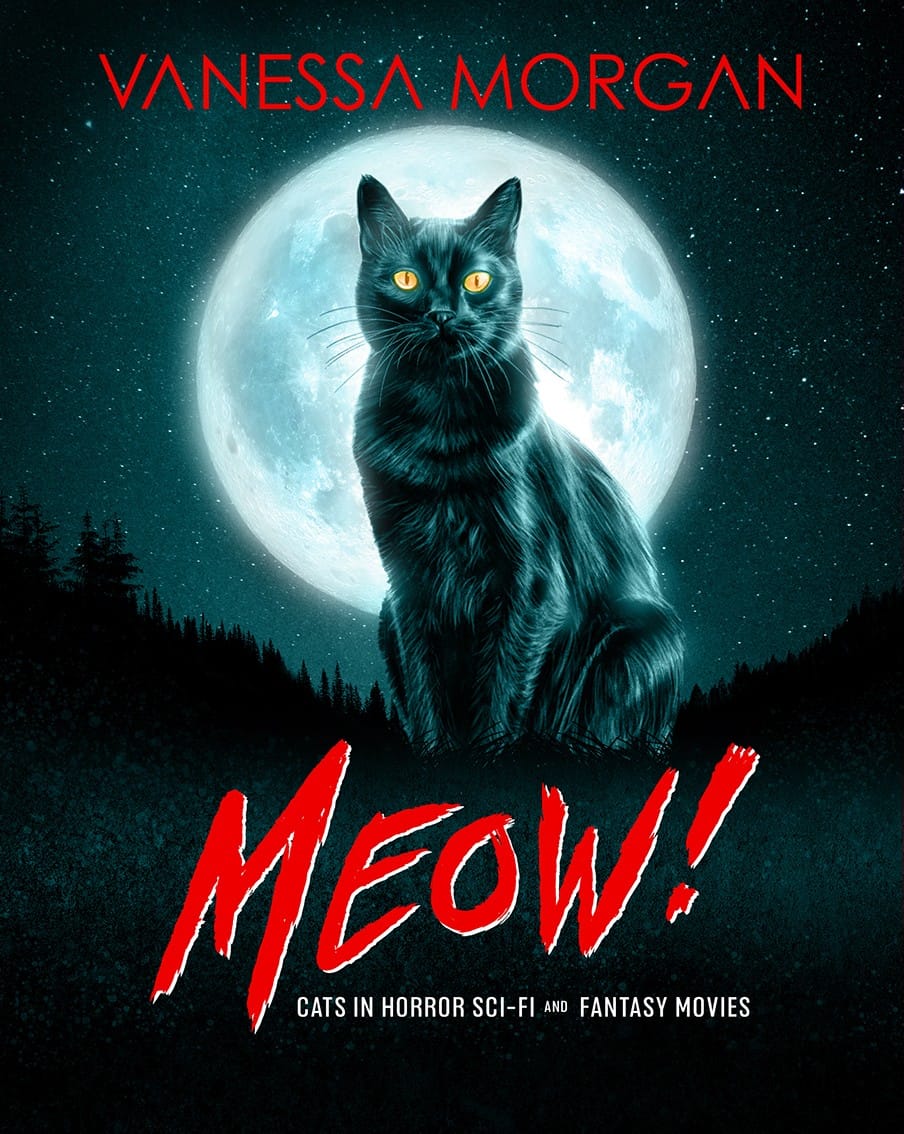

This review of Mr. Patman (1980) was previously published in the book Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies.

About the author

Vanessa Morgan is the editor of When Animals Attack: The 70 Best Horror Movies with Killer Animals, Strange Blood: 71 Essays on Offbeat and Underrated Vampires Movies, Evil Seeds: The Ultimate Movie Guide to Villainous Children, and Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies. She also published one cat book (Avalon) and four supernatural thrillers (Drowned Sorrow, The Strangers Outside, A Good Man, and Clowders). Three of her stories became movies. She introduces movie screenings at several European cinemas and film festivals and is also a programmer for the Offscreen in Brussels. When she is not writing, you will probably find her eating out or taking photos of felines for her website, Traveling Cats.

Images courtesy of Cinematek Brussels.