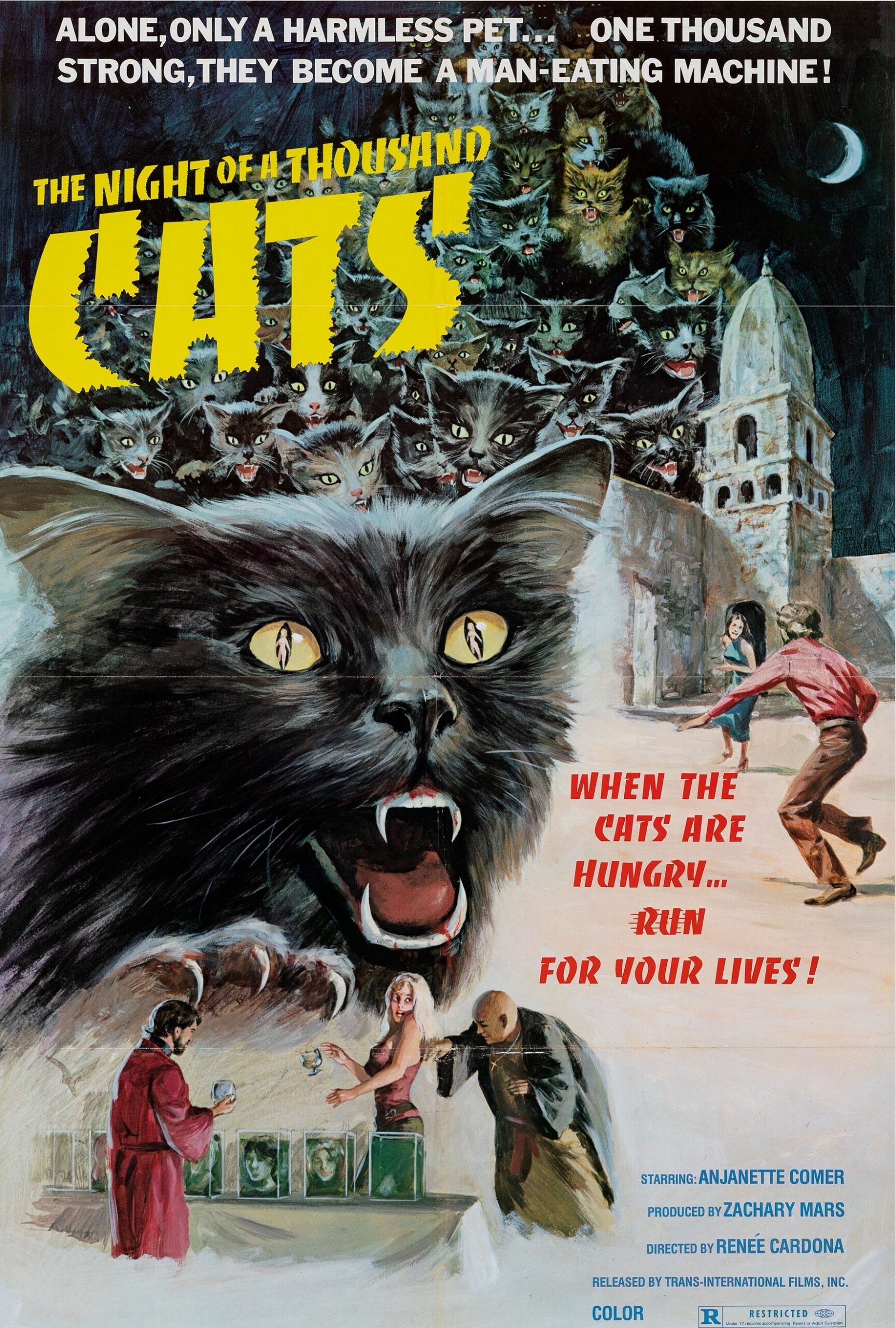

The Bizarre Horror of Night of a 1000 Cats (1972)

A wealthy, deranged playboy lures women to his gothic mansion—only to feed them to his army of ravenous cats in this bizarre, surreal slice of ’70s Mexican horror.

Night of a 1000 Cats

Original title: La noche de los mil gatos

Director: René Cardona Jr.

Country: Mexico

If director René Cardona Jr. remains infamous to this day, it is largely due to his use of real animals in distressing situations. In Tintorera: Killer Shark (1977), based on oceanographer Ramón Bravo’s novel, real sharks and manta rays were killed on camera. Cyclone (1978) also featured real sharks, but it is most notorious for a staged scene where a survivor cuts open a small dog’s throat and then uses the animal as food. In his most infamous film, Night of a 1000 Cats, the main character Hugo (Hugo Stiglitz from Umberto Lenzi’s Nightmare City, here also co-producing) grabs our favorite furry friends violently by the neck, flings them over a wall, throws them around, and drowns them in a swimming pool. Even seeing hundreds of them amassed together and running away in fear is enough to set the Animal Protection Society on alert!

Cardona was driven by the desire to create a more visceral and realistic experience for the audience, a hallmark of exploitation cinema, where shock and sensationalism are central. He pushed boundaries to stand out in a crowded market, using real animals in shocking ways to achieve notoriety. In the 1970s, this was possible due to the lack of stringent animal welfare regulations.

This exploitative approach to filmmaking, combined with poor acting and lack of coherence, is why Cardona’s work is heavily criticized and poorly distributed. Reviews on Letterboxd reflect this sentiment, with one user noting, “This has maybe 200 cats, and it’s a total snooze whenever they aren’t on screen,” and another stating, “Objectively a bad movie, made worse by some obvious animal mistreatment.”

However, not everyone is critical of Cardona’s work. Quentin Tarantino, for example, is a big fan, calling him “The Roger Corman of Mexico.” Admittedly, Cardona (along with Buñuel) has made more Mexican movies that have been theatrically released in America than any other Mexican director. His Jaws-inspired Tintorera: Killer Shark was particularly successful on the international market, with Night of a 1000 Cats being a close second.

Night of a 1000 Cats is by far the most outlandish of Cardona’s career. It stands out in the annals of horror for its bizarre premise and execution, firmly placing it within the niche of exploitation cinema.

The film starts on the beach of Acapulco, where a wealthy playboy named Hugo is on a date with a beautiful woman named Barbara (Barbara Angely). He tells her he is worried about how he is going to “finish something” and then takes her on a boat trip and drowns her.

In the next scene, Hugo is already on another date, this time with Christa (Christa Linder). Accompanied by romantic music and shown in slow motion, we see a montage of their activities: riding a horse on the beach, playing chess, running happily into the sea hand in hand, playing chess again, making love in a swimming pool, and enjoying each other’s company on his private yacht. When the montage ends, Christa tells him she came to Mexico to study anthropology, but now she wants to stay with him. He responds that he wants to keep her too… “somewhere where no one can touch you, like in a crystal cage.”

Using his helicopter, Hugo takes Christa to his secluded home, a castle and a 1600s convent he inherited. His mute, bald assistant, Dorgo (Gérardo Zepeda), prepares dinner—a piece of meat on a plate. Hugo remarks, “Dorgo is a great cook, and meat is his specialty.”

With so many dates and screen time behind them, the film has established who will become our final girl. Or has it? After dinner, Hugo shows Christa his collection of stuffed animals and human heads in glass jars. Then he strangles her and feeds her remains to the hundreds of feral cats in his cellar, only preserving her head as part of his “collection.” All of this is carried out with the help of Dorgo.

The entire film revolves around Hugo seducing and murdering women, with little else happening. Its brilliance lies in how it plays with structure and audience expectations, setting up the notion that one of these women will become the final girl, only to subvert this each time.

After Christa’s death, Hugo is back on the prowl in his helicopter, flying around Acapulco and observing beautiful women lounging on beaches or by their pools. He now sets his sights on two potential victims at a time: a married woman named Cathy (Anjanette Corner, known for The Baby) and a dancer (Zulma Faiad). Using his helicopter to seduce them, Cathy is the first to wind up in bed with Hugo at his castle. However, before he can add her to his collection, there is a knock at the door—a doctor on an emergency call has had car trouble. Cathy seizes this opportunity to leave, and Hugo kills the doctor instead.

Hugo then watches the dancer perform at a nightclub. They visit a local park, but Hugo falls asleep on a bench, and the dancer goes home alone. When he finally does hook up with the dancer at her house, she receives a phone call from “the person who pays for all this.” In a fit of rage, Hugo grabs her cat and drowns it in the swimming pool. Later, when Dorgo makes a good chess move, Hugo’s anger boils over, and he tosses his assistant into the cat dungeon as food.

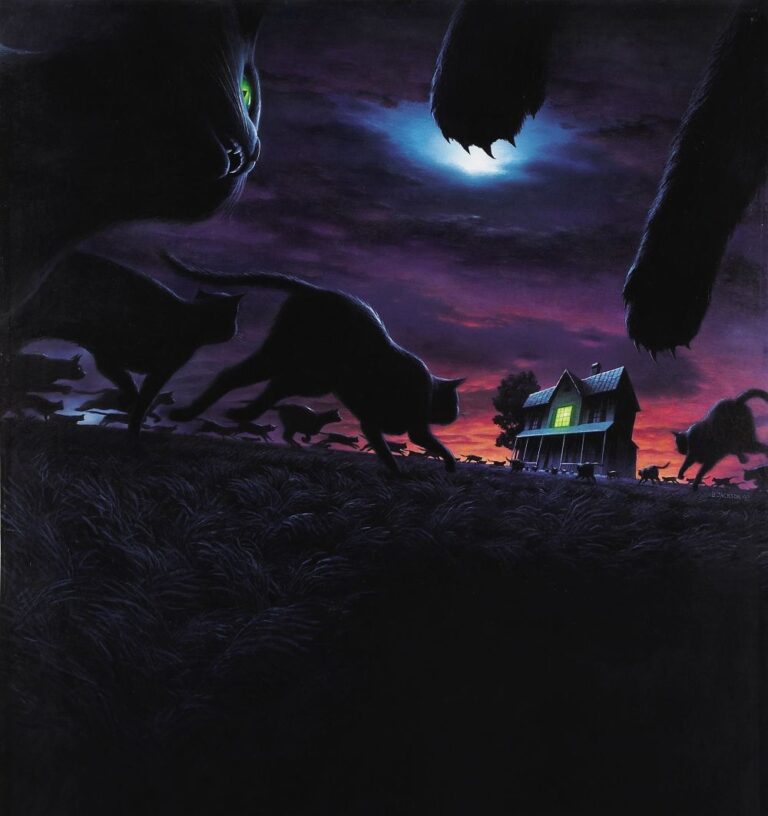

Hugo also takes Cathy’s little girl for a helicopter ride while her mother takes her husband to the airport for a business trip. Against the audience’s expectations, he returns the girl without harming her. Impressed by Hugo’s thoughtfulness with her daughter, Cathy agrees to a second date at his house. During the visit, Hugo shows her his collection of heads in jars. When Cathy recognizes Dorgo’s head among them, she throws a glass at Hugo and flees. She manages to escape the house and get into her car. The cats see this as their cue to escape and attack their master. The film concludes predictably, with the cats eating Hugo.

Regardless of opinion, putting this film into a historical perspective is interesting. When Cardona made Night of a 1000 Cats, the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema had already passed. From the 1930s to the 1960s, it marked significant growth and international acclaim for Mexican films. Movies from the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema were known for their technical proficiency, with notable improvements in sound, lighting, and cinematography. They often reflected Mexican culture, traditions, and societal issues, contributing to a solid national identity. These films gained popularity domestically and in other Spanish-speaking countries and beyond, winning awards at international film festivals. The director’s father, René Cardona, was a significant figure during this period, contributing to the Golden Age with notable works like Santa (1932), considered one of the first sound films in Mexico, and Nosotros los Pobres (1948), a classic of Mexican cinema featuring Pedro Infante.

The Golden Age of Mexican cinema coincided with a time of strict censorship in the country, primarily influenced by the Catholic Church and political figures like Presidents Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946) and Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946-1952), who prioritized nationalism and moral conservatism.

But when the 1970s arrived, classic Mexican cinema had largely come to a halt. This decline began in the late 1950s and early 1960s when Mexico faced severe economic challenges. Financial constraints led to smaller budgets for film production. In turn, this reduced both the quality and quantity of the cinematic output. Meanwhile, American films, both Hollywood productions and exploitation films, dominated the Mexican market, and the rise of television offered new entertainment options that competed with movies.

With tighter budgets and the influence of American exploitation cinema, Mexican filmmakers began producing more shock-value films. They were cheaper to make and often more profitable. Censorship also eased in the late 1960s and early 1970s. President Luis Echeverría (1970-1976) adopted more progressive policies in response to social unrest and demands for greater freedoms. This environment allowed filmmakers like Cardona to capitalize on these changes.

However, despite its low budget and exploitative style, Cardona knew what he was doing, and thanks to connections through his father, he was able to persuade key figures in the Mexican film industry to work with him.

The Canadian-Mexican cinematographer Alex Phillips, for example, was a significant figure in the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema and worked on over 200 films, including En La Palma de Tu Mano (1951), Canoa (1976), and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974).

Another important member to have joined the set of Night of a 1000 Cats was Raúl Lavista, a prolific Mexican composer whose career spanned several decades, during which he composed the soundtracks for over 300 films. Lavista’s compositions were integral to the atmospheric and emotional impact of many films across various genres, including drama, horror, and comedy. His musical impact on Night of a 1000 Cats was particularly significant, as much of the film is without dialogue. Reminiscent of the soundtracks of many Italian exploitation movies from the 1970s, his input played a crucial role in setting the tone and atmosphere.

One of the film’s stand-out elements is the experimental editing by the award-winning Alfredo Rosas Priego, who also worked with Cardona on The Bermuda Triangle (1978) and Cyclone (1978). He intercuts lovemaking scenes with images of stuffed animals, lingers on shots of the sun in unexpected places, and shows the clowder of yowling, hungry cats whenever Hugo contemplates killing someone, even if his actions are unrelated.

Night of a 1000 Cats is genuinely a curiosity in exploitation cinema and worth checking out for its unique experimental style and use of hundreds of cats. However, be aware that the scenes of cat cruelty and misogyny may upset many viewers.

It is also essential to know that two distinct versions exist. The original Mexican cut from 1972 runs 93 minutes, while the American version, released in 1974, is edited down to 63 minutes.

This Night of a 1000 Cats review was previously published in the book Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies.

About the author

Vanessa Morgan is the editor of When Animals Attack: The 70 Best Horror Movies with Killer Animals, Strange Blood: 71 Essays on Offbeat and Underrated Vampires Movies, Evil Seeds: The Ultimate Movie Guide to Villainous Children, and Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies. She also published one cat book (Avalon) and four supernatural thrillers (Drowned Sorrow, The Strangers Outside, A Good Man, and Clowders). Three of her stories became movies. She introduces movie screenings at several European cinemas and film festivals and is also a programmer for the Offscreen Film Festival in Brussels. When she is not writing, you will probably find her eating out or taking photos of felines for her website, Traveling Cats.

Pin the Night of a 1000 Cats movie poster!