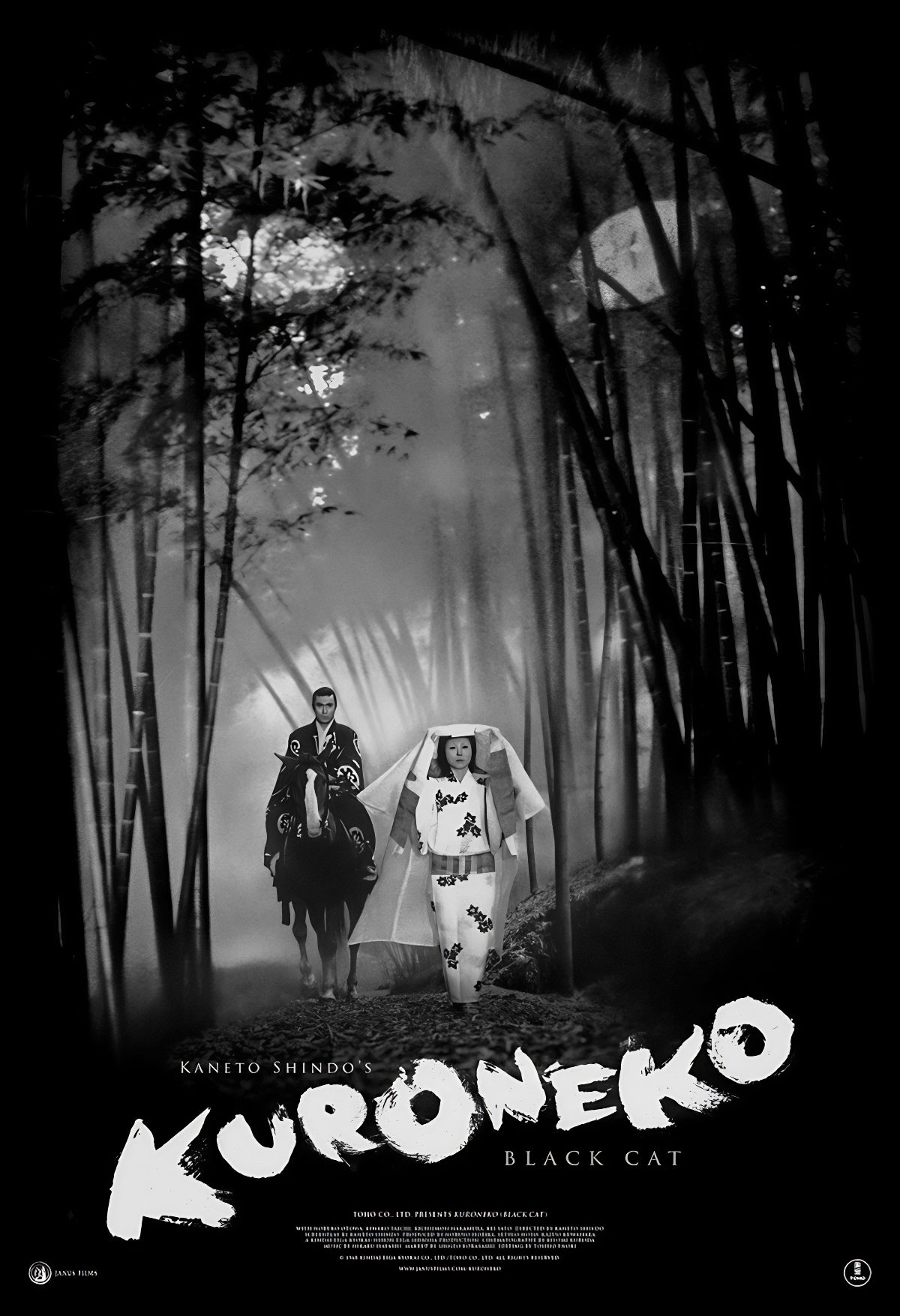

Kuroneko (1968)

Kuroneko (1968) is an iconic Japanese horror film where two vengeful spirits haunt samurai in a bamboo grove.

Kuroneko

Original title: Yabu No Naka No Kuroneko

Director: Kaneto Shindô

Country: Japan

Kaneto Shindô’s terrific companion piece to his highly-regarded Onibaba (1964) is one of the finest ghost movies of the decade. Gintoki (Kichiemon Nakamura) is conscripted to fight in a feudal war. While awaiting his return, a band of passing samurai invade the country house of his mother, Yone (the excellent Nobuko Otowa, returning from Onibaba), and his wife, Shige (Kiwako Taichi). The samurai steal their food and water, assault and murder them, and then destroy their home. A black cat appears and licks their corpses, which marks the beginning of their return from the dead as vampiric ghosts seeking revenge. They return to human form in exchange for killing and drinking the blood of every samurai they happen to come across. Their new cat-like traits—such as stealth and a predatory nature—make them effective at luring and killing samurai. Throughout the film, the presence of the black cat enhances the eerie and otherworldly atmosphere, reminding us of the supernatural forces at work. The cat’s connection to Shige is solid, often appearing when she is about to strike. (In Japanese, “kuro” means black, and “neko” stands for cat.)

Late at night at Rajomon Gate, the village’s main square, Shige waits patiently for any chivalrous samurai passing through and asks if they will accompany her home. She leads them down a long, dark path, invites them inside, gives them enough sake to get drunk, tempts them with sex, and then, along with Yone, kills them by chewing out their throats like stealthy, cat-like seductresses.

Meanwhile, Gintoki returns home and finds his house charred and his family missing. Now a war hero and high-ranking samurai after slaying a mighty barbarian, Gintoki is hired by the village’s prejudiced police chief, Raiko (Kei Sato, also from Onibaba), to kill those responsible for the recent samurai slayings.

While patrolling Rajomon Gate one evening, Gintoki comes across a veiled Shige, who lures him back to her spectral home. Though Shige and Yone try to hide their identities at first—a pact with the evil God states they cannot reveal who they are or why they are killing samurai, or else face eternity in hell—Gintoki soon realizes he has found his missing family. Shige takes a huge risk by engaging in a passionate affair with her ex-husband instead of seeking revenge. At the same time, Gintoki faces an ultimatum from Raiko: either kill the women or be killed himself.

Many of Kuroneko‘s themes—revenge, ghosts, black cats, loyalty to family, and class status—are common in Japanese cinema. However, Shindô brings a highly personal and stylish touch to these elements.

It is essential to know that Shindô was part of the Japanese New Wave of the 1960s, though he stayed more in the background, contrary to leading figures like Nagisa Ōshima or Shōhei Imamura. Unlike the classic films of directors like Yasujirō Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi, which often focused on timeless themes of family, honor, and societal duty within a formal narrative structure, the New Wave filmmakers introduced provocative and contemporary subjects. They tackled political disillusionment, generational conflict, social inequality, and individual identity in a rapidly changing society.

In the case of Kuroneko, this translates into deconstructing the myth of the samurai, stripping down a profession once unthinkingly regarded as noble and respectable and turning it into something shaded. Just like many others in high-ranking positions, samurai frequently misused their power, using their status as justification to terrorize and commit crimes against people they considered inferior or disposable, such as farmers, peasants, and women.

Shindô was particularly interested in rural life, specifically the lives of farmers and the social issues they faced. This stemmed from his background: his family were once large landowners with ties to samurai families, but they lost their status and became peasants. Because of this background, both his films Onibaba and Kuroneko delve into the living conditions of rural people during the Edo period.

In addition to his social commentary, Shindô incorporates a feminist perspective into Kuroneko by critiquing feudal Japan’s patriarchal, macho society and portraying women as empowered avengers rather than passive victims. Notably, one of his mentors, Kenzo Mizoguchi, a renowned director of classic Japanese cinema, shared similar concerns regarding gender roles and societal critique.

The motif of black cats licking corpses and women who transformed into cats or had affiliations with cats to seek revenge is a much more prevalent trope in Japanese culture. It originates from traditional tales dating back to the Edo period (1603-1868). These stories, such as “The Cat’s Revenge,” often began as oral traditions associated with specific clans but were later included in various literary collections of ghost stories. Another famous example is “The Bakeneko of Nabeshima,” which is linked to the Nabeshima clan, a powerful samurai family in the Saga Domain during the Edo period. This story is recounted in Lafcadio Hearn’s book Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, published in 1904.

However, Shindô’s film is probably the definitive entry in the “bakeneko” (cat demon) subgenre of Japanese horror cinema, which also includes Kunio Watanabe’s Ghost-Cat of Arima Palace (1953), Nobuo Nakagawa’s The Mansion of the Ghost Cat (1958), and Yoshiro Ishikawa’s The Ghost Cat of Otama Pond (1960). Shindô revitalizes this recurring theme with a fresh approach, employing a dynamic and experimental filmmaking style influenced by Western avant-garde movements such as the French New Wave. Techniques such as non-linear storytelling, unconventional editing, handheld cameras, and symbolic imagery take center stage, challenging traditional cinematic norms and resonating with a younger, more politically aware audience.

Kuroneko is superbly photographed in black and white by Kiyomi Kuromi, who won the prestigious Mainichi Film Award for his work on both Kuroneko and Onibaba. The black cat creates a striking contrast against the white forms of Yone and Shige, accentuating themes of life and death, innocence and vengeance.

The lighting is highly stylized, with some images spot-lit to stand out. Cinematic techniques, such as close-ups and stark lighting, emphasize the cat’s significance and enhance the film’s haunting atmosphere. Additionally, Japanese theatrical traditions are very much to the fore here, with Noh elements in some of the staging and choreography and kabuki influence on the aerial acrobatics of the cat spirits.

Takashi Marumo’s art direction is clever and exceptional, especially in the ladies’ spectral home. This is achieved with a symmetrical and vertical theme that nearly blends the interiors with the thick bamboo fields surrounding the house.

Regarding the cats, there are imaginative touches, too, such as glimpses of hair on Shige’s arm or her hair swishing like a cat’s tail.

Kuroneko is also well-acted by all four principals, and the characters have enough conflicts of conscience to keep the emotional content compelling. The horror and supernatural elements are eerie, sometimes jarring even.

Find Kuroneko (1968) on Amazon!

About the authors

Justin McKinney was coerced over to the dark side by a late-night viewing of Night of the Living Dead (1968) as a child. He has worked on and appeared in several low-budget horror films (Descend into Darkness 1 and 2, Brain Drain,Loonies, Dance of the Dead, Fatal Delusions, Witch Graveyard, Chubby Killer, Slice N Dice, Phantom Limb, Day of 1000 Screams, and others) and has contributed reviews to numerous websites, magazines, and books, including Horror 101: The A-List of Horror Films and Monster Movies, Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, When Animal Attack: The 71 Best Horror Movies with Killer Animals, Evil Seeds: The Ultimate Movie Guide to Villainous Children, Seminal Cinema, Horrorpedia, and his blog, The Bloody Pit of Horror. His original screenplay, One Last Photo, is part of the horror anthology Screams of a Summer Day.

Vanessa Morgan is the editor of When Animals Attack: The 70 Best Horror Movies with Killer Animals, Strange Blood: 71 Essays on Offbeat and Underrated Vampires Movies, Evil Seeds: The Ultimate Movie Guide to Villainous Children, and Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies. She also published one cat book (Avalon) and four supernatural thrillers (Drowned Sorrow, The Strangers Outside, A Good Man, and Clowders). Three of her stories became movies. She introduces movie screenings at several European cinemas and film festivals and is also a programmer for the Offscreen in Brussels. When she is not writing, you will probably find her eating out or taking photos of felines for her website, Traveling Cats.

This movie review was previously published in the book Meow! Cats in Horror, Sci-Fi, and Fantasy Movies.

$25 Amazon Gift Card Giveaway

Enter this $25 Amazon Gift Card to celebrate the pre-order release of Meow! For a chance to win, fill out the Rafllacopter below. The giveaway is open worldwide and ends February 25, 2025. Good luck!

a Rafflecopter giveawayPin the Kuroneko movie poster!